Small Savings Schemes (SSS) serve a large section of our country. For perspective, the quantum managed in National Small Savings Fund (NSSF) is approximately Rs 25 lakh crore. Given the small ticket size of these schemes, they serve a large chunk of the population.

The interesting thing though is to understand how the interest rates in these schemes are set. That would give a perspective on why upward revision over the medium term is a possibility.

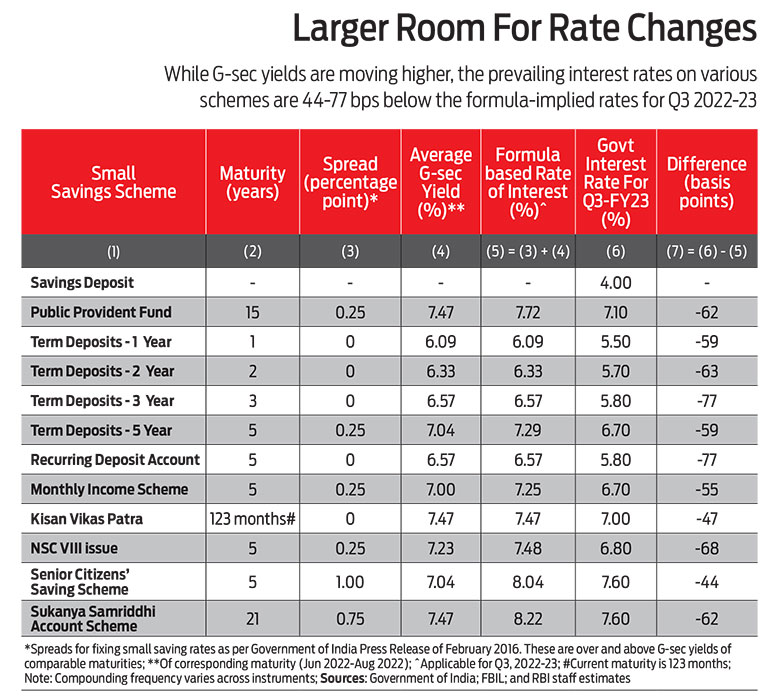

The interest rates on these schemes are reviewed every quarter, and announced on the last day of the quarter for the next quarter. There is also a reference benchmark for this exercise, which is the level at which government securities (G-secs) are traded in the secondary market. The rationale for linking these to G-sec yields in the secondary market is to keep them aligned with the interest rate trends.

G-sec yield movements reflect the actual and anticipated events in the economy pertaining to the interest rate movement. Government bond yields of commensurate maturity are considered as the maturity of the SSS.

There is also a pre-decided spread (higher yield) for SSS over the relevant G-sec level. The rate of interest is aligned to the G-sec yields of similar maturity with a spread of 25 basis points (bps), with certain exceptions. One hundred bps equal 1 per cent.

For instance, the spread on Senior Citizens’ Savings Scheme (SCSS) will be 100 bps over G-secs of comparable maturity. However, though the rates are reviewed and communicated every quarter, it is not followed strictly.

The government retains flexibility on setting the rate. The basis on which this is set is to be taken as a reference point and not a statute.

Earlier, over the last 2-3 years, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) maintained an easy monetary policy, and cut interest rates.

Accordingly, the rates on G-secs, which are the traded yield levels in the market, went down. The last rate revision in SSS was done on March 31, 2020, for the quarter April-June 2020, when rates were slashed. Thereafter, rates were reviewed and announced for every quarter, but were left unchanged. It would seem like a non-event as there was no change in the rates. However, changes were happening internally, forming the basis of having no revisions.

As traded levels of G-secs in the market were coming down, and SSS rates were maintained, the spreads were moving up. That is, the spreads were much higher than the formula set by the government.

In other words, while the government could have cut SSS rates according to the formula, it did not do so. It was a measure of public welfare, as SSS, typically, serve the people who are not so financially well off. It may be argued that there was a political angle in not reducing SSS rates. Nevertheless, the people benefitted from it.

As an illustration, for the April-June 2021 quarter, the formula rate for the National Savings Certificate (NSC) VIII Issue, which is at a mark-up of 25 bps, would have been 5.88 per cent. It was, however, maintained at 6.8 per cent, implying a higher-than-required spread of 92 basis points.

In April-June 2021, the higher-than-required spread was 89 bps for SCSS. It was 198 bps for the 1-year term deposit, 94 bps for the 5-year term deposit, and 69 bps for Sukanya Samriddhi Yojana (SSY).

For the current quarter, October-December 2022, there have been minor upward revisions in rates.

The rates have been hiked by 10-30 bps in certain schemes, such as time deposits, post office monthly income scheme (MIS), and so on.

But the bigger picture is that there is a negative spread while comparing the announced rates with the formula rates. That is, the rates should have been higher, going strictly by the formula.

The negative spread is across the board. For example, for Public Provident Fund (PPF), it should have been 7.72 per cent, but it has been maintained at 7.1 per cent i.e., a negative spread of 62 bps. For term deposits, the negative spread is in the range of 59-77 bps. For NSC VIII Issue, it is 68 bps, for SCSS, it is 44 bps, and for SSY, it is 62 bps (see Larger Room For Rate Changes).

Conclusion

The probable reason why the government has not given the benefit this time is that for a long time, say eight or nine quarters, there was a positive spread, i.e. rates were higher than formula. At present, they have gone conservative on their side. But the negative spreads give us hope that in the medium term, there is scope for upward revision.

The counter-argument would be: what if the G-sec yields come down, and spreads become positive again? Well, nobody knows the future, but chances are less. RBI would hike interest rate to some more extent, and in the near to medium term, G-sec yields are unlikely to come down by any significant extent.

Source: https://www.outlookmoney.com/magazine/story/rising-g-sec-yields-signal-rate-hike-1187